One woman's inspirational tale about expressing joy amid

loss and suffering.

To Climb a Distant

Mountain:

A Daughter’s Tribute to Her Diabetic Mother

by Laurisa White Reyes

Genre: Historical True Memoir

In 1974, at the age of twenty-six, Cynthia Ball White was

diagnosed with Juvenile Diabetes. Today, it is estimated that 1.25 million

Americans suffer from what is now referred to as Type I diabetes, compared to

38 million who have Type 2 (adult onset) diabetes. It is a merciless disease

that often leads to blindness, neuropathy, amputations, and a host of other

ailments, including a shortened life span.

Despite battling diabetes for forty-five years, Cyndi beat

the odds. Not only did she outlive the average Type I diabetic, but until her

last week of life in 2021, she had all her “parts intact”. Her daughter often

called her a walking miracle. But more impressive was Cyndi’s positive outlook

on life, even in the midst of tremendous loss and suffering.

The author hopes that in sharing Cyndi’s story, others may

be inspired to face their own struggles with the same faith, courage, and joy

as her mother did.

Amazon

* B&N

* Bookbub

* Goodreads

I’m

going to tell you about my mother. Yes, that is the story I will tell. No other

story really matters. I know that now. Funny, how you can spend a lifetime

conjuring up magical tales of dragons and enchanters and heroes who will never

exist except in your own head and on sheets of paper, when the stories that

matter most happen every day all around us. I’ve spent most of my life making

up stories. It’s what I do. But now that Mom is gone, I have no stories left.

At least none that I care about more than hers.

My first distinct memory of my mother (I was five or six) was

in the hospital. I’d come to know that hospital well. It’s in Panorama City,

half an hour from where I live now, half an hour from where I lived then, two

different cities—two points on the circumference of a circle with the hospital

at its center. It’s where all five of my children were born, where my youngest

brother was born—and died. It’s where Mom would spend too much of her life. But

not yet. That would come later.

I remember the elevator doors opening and Dad pushing Mom out

in a wheelchair. She wore a yellow robe that a friend had bought her when she

got sick. She had crocheted me a hat. It was yellow too, criss-crossed strands

like a spider’s web, with a green band. She gave it to me there. I wore

it often as a child. Somewhere, I have a picture of me wearing it. The hat is

in my mother’s hope chest now, the one she passed on to me when I got married.

Been in there for years. Decades. It’s still a treasure.

I remember her disappearing back inside the elevator, waving,

the doors sliding shut, swallowing her. I still feel sick, tight and hollow

inside, when I think of that memory.

In the weeks leading up to that hospital stay, which would be

the first of dozens, she’d been sick. She’d lost weight and

felt very ill. She thought she was dying of cancer, but she postponed seeing a

doctor because she had recently enrolled in Kaiser Permanente medical insurance

through Dad’s employer, and she thought they had to wait for their membership

cards to come in the mail. By the time she walked into the ER, she was on death’s

door.

Her doctor smelled her breath, which Mom thought was an odd

thing to do. And then he called in other doctors to smell her breath. It

smelled sweet, like decaying fruit. Mom was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes,

which they used to call Juvenile Diabetes. It meant that her pancreas had

completely malfunctioned, and she would be insulin-dependent the rest of her

life. She learned how to give herself insulin by injecting oranges. She was

twenty-six years old.

Mom actually felt relieved because it wasn’t

cancer. There was no way to know then what diabetes would do to her, how it

would shape not only her life but the lives of her husband and children and

grandchildren, how it would gradually destroy her body a little at a time until

it finally robbed her of life itself.

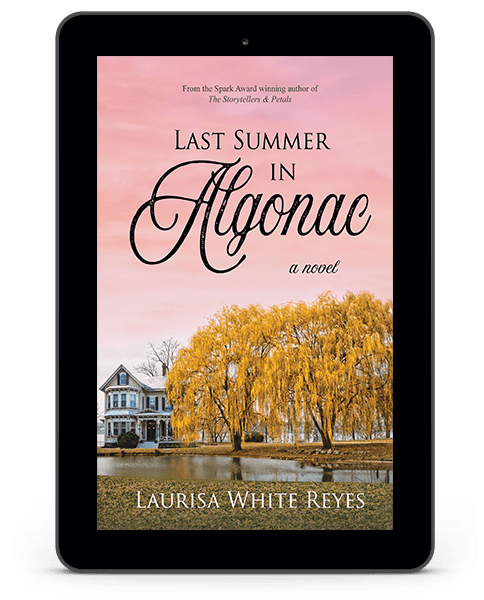

Last Summer in

Algonac

by Laurisa White Reyes

Genre: Fictionalized Family Biography

From the Spark

Award-winning author of The Storytellers & Petals...

The summer of 1938 is idyllic for fourteen-year-old Dorothy

Ann Reid. She’s spent every summer of her life visiting her grandparent’s home

on the banks of the St. Clair River in Algonac, Michigan. But unbeknownst to

her, this will be her last. As Dorothy and her family pass their time swimming,

fishing, and boating, they are blissfully unaware that tragedy lurks just

around the corner.

Last Summer in Algonac is a fictionalized account of the author’s grandmother

and her family’s final summer before her father’s suicide, which altered their

lives forever. Inspired by real people and events, Laurisa Reyes has woven

threads of truth with imagination, creating a “what if” tale. No one living

today knows the details leading to Bertram Reid’s death, but thanks to decades

of letters, personal interviews, historical research, and a visit to Algonac,

Reyes attempts to resolve unanswered questions, and provide solace and closure

to the Reid family at last.

Amazon

* B&N

* Bookbub

* Goodreads

That last

summer in Algonac, there was little water play for Father, who was now

fifty-seven. Alberta, who had married less than two years earlier and had

recently given birth to her first child, had opted to stay in Cleveland. She

and Charles had been my grandest playmates while I was growing up, but now they

both had new adult lives and families of their own. Even Charles, who was

eleven years my senior (Alberta fourteen years), would prove too occupied with his

wife Alice and their baby to venture into any games with me. I supposed Father

might have played that role with me when I was young, but I was thirteen now,

practically a woman, and neither he nor I dared suggest something so childish

as to jump into the river for a splash—except for that one last wonderful

afternoon.

Looking back, I

wish that I had done it every day—that I had taken his hand and walked with him

along the bank under the trees, or sat in the grass and taken off our shoes,

letting our feet dangle in the chilled, meandering water. I wish that I had had

the courage to ask him more about that old rowboat, whether he had ever taken

it all the way across the river to Ontario, Canada, where he and his family had

come from originally. I would have liked to have been in that boat with him

rowing, his muscles taut under his shirt, his sleeves rolled to the elbow.

We wouldn’t

have talked much. Father was a man of few words. But I would have listened to

the ripples of the St. Clair lapping against the boat, the gentle cut of the

oars through the water, the calls of birds overhead. It would have been enough

just to be with him, to see his face turned to the sun, the light glinting off

his spectacles, and to have seen traces of a smile on his lips.

1939, the year

Father died, was a big year for America. It was the year the World’s

Fair opened in New York, and the first shots of World War II were fired in

Poland. The Wizard of Oz premiered at Groman’s

Chinese Theater in Hollywood, California, and Lou Gehrig gave his final speech

in Yankee Stadium. Theodore Roosevelt had his head dedicated on Mt. Rushmore,

and John Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath. All in all, it was a monumental year,

one I would have liked to have shared with my father. He did live long enough

for Amelia Earhart to be officially declared dead after she disappeared over

the Atlantic nearly two years earlier, but otherwise, he missed the rest of it.

No child should

have to mourn a parent. And if she does, at least things about it should be

clear. Unanswered questions that plague one for the rest of one’s

life shouldn’t be part of the picture.

Death is

normally simple, isn’t it? Someone has a heart attack,

or dies in a car accident, or passes away in their sleep from old age. Everyone

expects to die sometime, and they wonder how it will happen and why. And when

it does, as sad as it is for those left behind, the wonder is laid to rest.

Most of the

time.

1939 was a

blur. I’d prefer to forget it, quite frankly. But 1938 was worth

remembering, especially that summer we spent in Algonac with Grandmother Reid

and the family. As long as I could remember, we’d spent every summer on the

banks of the St. Clair. As it turned out, it would be my final summer in

Algonac. Our last summer together. Of course, I didn’t know it at the time, and

I’m glad. If I could have seen seven months into the future, if I had known

then how the world as I knew it would all come crashing down, it would have

spoiled everything.

Laurisa White Reyes is

the author of twenty-one books, including the SCBWI Spark Award-winning

novel The Storytellers and the Spark Honor recipient Petals.

She is also the Senior Editor at Skyrocket Press and an English instructor at

College of the Canyons in Southern California. Her next release, a non-fiction

book on the Old Testament, will be released in August 2026 with Cedar Fort

Publishing.

No comments:

Post a Comment